, by NCI Staff

The number of people who die each year from the skin cancer melanoma has dramatically decreased in recent years, results from a new study show.

Beginning in the mid-1980s, death rates from melanoma showed a consistent rise. But from 2013 to 2016, the new study found, the number of deaths from melanoma among whites fell by about 18% overall. The sharpest decline was seen in white men aged 50 or older.

“This roughly 5% drop per year over 4 years is the largest drop ever seen over such a short period, for any kind of cancer,” said Allan Geller, M.P.H., R.N., of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, who co-led the study.

The decline likely was due, in large part, to a wave of new treatments, including targeted therapies and immunotherapy, approved for advanced melanoma over the last decade, the authors explained in a study published March 19 in the American Journal of Public Health.

And treatments for melanoma have only continued to improve over the last several years, said Anthony Olszanski, M.D., codirector of the Melanoma and Skin Cancer Program at Fox Chase Cancer Center, who was not involved with the study.

“I think that if we take another look at the data in a few years, we’re going to see an even bigger improvement than we saw in this study,” Dr. Olszanski added.

A Rapidly Changing Treatment Landscape

Starting in 2011, two new types of drugs started to change the treatment landscape for metastatic melanoma.

One was a group of targeted therapies called BRAF inhibitors and MEK inhibitors. The BRAF and MEK proteins are both part of a cell signaling pathway that commonly drives the growth of melanoma. The other was a type of immunotherapy called immune checkpoint inhibitors, which encourage the body’s own immune system to attack cancer cells.

In 2011, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the immune checkpoint inhibitor ipilimumab (Yervoy), the first drug to improve how long people with metastatic melanoma lived.

“And in a very short amount of time since then, more than 10 drugs have been approved [to treat metastatic melanoma], which have now been shown to improve overall survival in a very meaningful way,” said Dr. Olszanski.

Both BRAF and MEK inhibitors, which are typically used in combination, and immunotherapies can cause dramatic and sometimes long-lasting tumor responses in some people with advanced melanoma. However, the overall impact of these drugs on survival in people with melanoma was not clear.

To understand how these new therapies might have affected melanoma mortality nationwide, Geller and his team analyzed melanoma incidence and mortality data from NCI’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program collected between 1986 and 2016. The nine SEER registries used to estimate mortality cover about 10% of the US population. The areas covered are representative of the demographics of the national population.

Because more than 90% of melanomas occur in white men and women, the researchers only had enough data to analyze these groups.

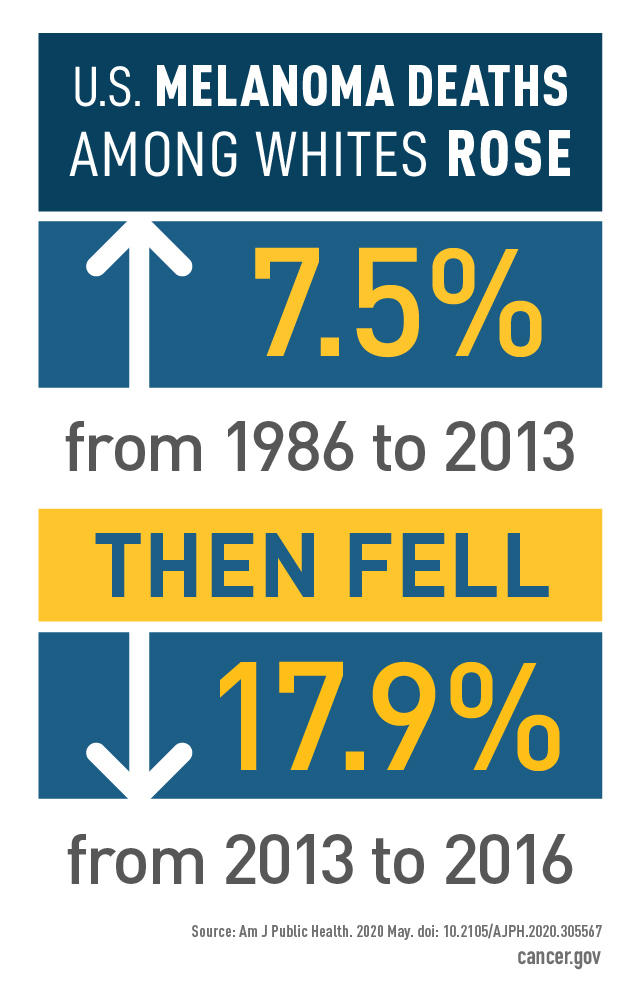

The researchers found that between 1986 and 2016, the number of new melanoma cases per year in whites aged 20 and older more than doubled. And, until 2013, the melanoma mortality rate in whites had also been rising. Overall, melanoma mortality increased by 7.5% between 1986 and 2013. For white men aged 50 and older, the increase was particularly sharp: more than 35%.

But from 2013 to 2016, the trends in mortality reversed. Overall, the melanoma mortality rate declined by 17.9% during the 4-year period. The reduction in deaths was seen in nearly every age group, but was greatest in men aged 50 and older.

“Across the whole country, by 2013 to 2014, we really began to see a population-wide decrease [in melanoma mortality],” Geller said.

Additional treatments for melanoma have been approved by FDA since 2016, the last year included in the study, explained Dr. Olszanski. With immunotherapy combinations now regularly being used for these patients, “we expect half of them to be alive 5 years [after starting treatment],” a number unheard of only a decade earlier, he said.

The large mortality reductions seen in the study were observed during a time when only a minority of people with metastatic melanoma likely received the new drugs, explained Geller. Although they have since become more widely used, cost and access are still barriers for many patients, he said. Many of the newer therapies cost substantially more than $100,000 per year, and insurers don’t always cover the full cost, he added.

“The big issue now in melanoma is equitable drug delivery,” said Geller. “Lack of insurance should not make it difficult for patients to be treated with these new drugs.”

An Ounce of Prevention

Much more could also be done to prevent and detect melanoma early, said Geller. Many melanomas could be prevented by protecting the skin from excess ultraviolet (UV) radiation exposure, added Dr. Olszanski.

“We really need to be more vigilant about applying sunscreen and trying to stay out of the sun,” especially during late morning to early afternoon, when the exposure is more intense, he said.

“As we always say, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. We have ‘a pound of cure’ right now with immunotherapies and targeted therapies,” said Dr. Olszanski. “These drugs are making a meaningful impact on overall survival, but it would be best to try to avoid [melanoma] altogether, if possible. The way that we do that is with good sun exposure habits.”

Recent public health efforts have also focused on educating people about the dangers of using indoor tanning beds, another source of UV exposure for the skin. In many states, laws have been passed that prohibit or restrict the use of indoor tanning facilities by people under the age of 18. Between 2009 and 2017, the use of indoor tanning devices by youths in grades 9 through 12 dropped, suggesting these efforts may be paying off.

In addition, other recent data have shown that “for the first time, the incidence of melanoma among people between the ages of 20 and 29 has actually gone down,” said Geller. “That gives us a sense that all of these primary prevention messages that have been out there the last 20 years are very slowly beginning to have an impact.”

Additionally, encouraging people—especially middle-aged and older white men—to regularly check their skin for suspicious moles could help detect more cases of melanoma at an earlier stage, Geller said. “If more people did that, then fewer people would need treatment for advanced disease.”