, by Sharon Reynolds

Weight-loss surgery, also known as bariatric surgery, can help many people lose a lot of weight and reduce the risk of obesity-related health problems like diabetes and heart disease.

According to a new study, it may also provide an additional benefit: substantially reducing the risk of some common cancer types.

Prior studies have found that bariatric surgery may reduce the risk of developing some cancers associated with changes in hormone levels, such as postmenopausal breast cancer, endometrial cancer, and ovarian cancer. But whether it does the same for other types of cancers not usually driven by hormones, like liver cancer and colorectal cancer, hasn’t been clear.

In this new study, researchers analyzed the results of previous studies that looked at cancer risk in more than 18 million people with obesity. Of these, almost a million had undergone bariatric surgery. The researchers found that people with obesity who had bariatric surgery had a substantially lower risk of developing five types of solid tumors that are not related to hormone levels over the next several years. The results were published on October 19 in the British Journal of Surgery.

“Bariatric surgery is a safe and effective procedure, not just for weight loss, but also for reducing the risk of other diseases associated with obesity,” including diabetes, hypertension, sleep apnea, and acid reflux, said the study’s leader, Omar Ghanem, M.D., of the Mayo Clinic.

“Quality of life is also increased after bariatric surgery. And now we know that it’s associated with a decreased risk of [both] hormonal and non-hormonal cancers.”

Because the study, a type known as a meta-analysis, included data from multiple earlier studies, it has some limitations, explained Edward Sauter, M.D., Ph.D., of NCI’s Division of Cancer Prevention, who was not involved with the study. These limitations include difficulty accounting for all the factors that could influence the results one way or another.

And these new results raise even more questions, such as whether some people—including those of specific sex, racial, or ethnic groups—may benefit more from the surgery than others in terms of cancer risk reduction.

“Many reports indicate that obesity will soon surpass tobacco smoking as the biggest preventable cause of cancer,” said Dr. Sauter. “So there is a need to better understand how metabolic and bariatric surgery impacts cancer risk.”

Why does obesity increase cancer risk?

People with obesity have an increased risk of at least 13 types of cancer. The processes in the body thought to drive this higher risk are varied, and researchers still don’t fully understand the basis for the association.

For hormone-driven cancers, the link is fairly clear. Obesity increases the production of hormones that these cancers hijack to fuel their growth. It also decreases the production of other molecules that can keep these and other hormones in check.

Obesity also increases chronic inflammation in the body, which is thought to lead to chronic stress in cells and, eventually, damage to DNA. This can elevate the risk of cancer. But although weight loss after bariatric surgery is associated with a reduced risk of hormonally driven cancers, whether the surgery can reduce this more general type of risk hadn’t been clear from scattered single studies.

To find answers, Dr. Ghanem and his colleagues screened more than 2,500 previously published studies that looked at people who underwent one of three types of bariatric surgery between the 1980s and the late 2010s with people with obesity who didn’t have surgery. (See table at end of story on types of bariatric surgery.)

Of these, 15 studies included enough detail about their participants to be included in the meta-analysis. On average, people in the studies were followed for about 5 years. The median age of people included in the studies was 47 years old, about two-thirds were women, and most had severe obesity.

A reduced risk of five cancer types

Overall, Dr. Ghanem and his colleagues reported, substantially fewer people who had bariatric surgery were diagnosed with cancer over the next few years than people with obesity who didn’t have surgery. When Dr. Ghanem and his team broke this down by cancer type, study participants had a reduced risk of 5 of the 10 tumor types examined: liver, colorectal, kidney and urinary tract, esophageal, and lung cancer.

When the researchers looked at the risk reduction by type of surgery, the two types used most commonly today, gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy, were both associated with a reduction in overall cancer risk; but gastric banding, an older procedure that is rarely used in the United States today, was not.

This difference may be due to the surgeries having different effects on the body, said Dr. Ghanem.

While gastric banding simply promotes weight loss, the other two procedures are thought to have immediate and direct effects on metabolism, including a reduction in certain molecules associated with inflammation, he explained.

“That can probably add to the effect of surgery and to how bariatric surgery is related to a decrease in cancer: it’s [likely] not just the weight loss,” he said.

Looking for the ‘why’ behind cancer risk reduction after bariatric surgery

The study couldn’t tease out any of the “whys” behind the lower cancer risk in people who had bariatric surgery and lost a lot of weight, said Dr. Sauter. Other, smaller studies have found different trends, such as a potential increased risk of colon cancer after gastric bypass, he explained. That raises the question of whether the type of bariatric surgery plays a role.

Another intriguing question is why most other studies have found that women tend to have a greater reduction in cancer risk after bariatric surgery, explained Dr. Sauter. “Is this because of the types of cancer that are impacted, or is it something else?” he asked.

Future studies should look at how the risk of cancer changes over time after bariatric surgery, said Dr. Ghanem. The current meta-analysis had data from only about 5 years after surgery, and less for many people. “Usually for cancers to go from minimal [cellular] changes to full-blown cancer takes more time,” he explained.

For now, he hopes that these results might make more doctors consider bariatric surgery for their patients.

Currently, only 1% of people with obesity in the United States have bariatric surgery, he said.

“That’s a pretty small number, relative to the huge disease burden we have,” Dr. Ghanem said. “I wish [weight loss] was just about what you eat and how much you move, but it’s not. It’s much more complex than that.”

| Type of bariatric surgery | How it works |

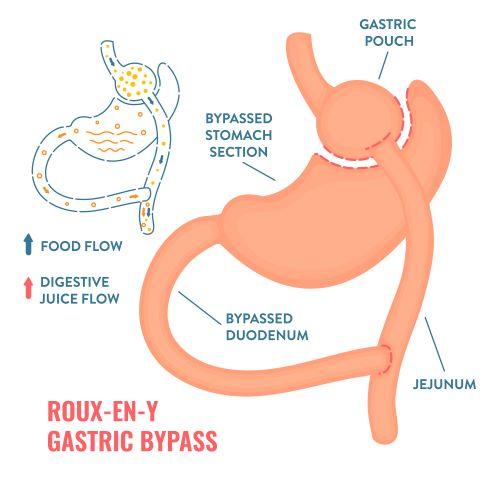

| Roux-en-Y gastric bypass | The surgeon places staples in the stomach, creating a small pouch in the upper section. The stapling makes the stomach much smaller, so the person eats less because they feel full sooner. In addition, part of the small intestine is divided and attached directly to the small stomach pouch. Because food will bypass most of the stomach and the upper part of the small intestine, the body will absorb fewer calories. |

| Sleeve gastrectomy | The surgeon removes most of the stomach, leaving only a banana-shaped section that is closed with staples. The surgery reduces the amount of food that can fit in the stomach, making the person feel full sooner. |

| Gastric banding (rarely used in United States today) | The surgeon places a ring with an inner inflatable band around the top of the stomach to create a small pouch. The gastric band makes the person feel full after eating a small amount of food. |

Adapted from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases: Types of Weight-loss Surgery.